Old Norse weak verbs and dental suffix (2)

Old Norse grammar | Weak verbs | Old Norse phonology | Proto-Germanic

The Old Norse preterite and past participle of weak verbs is formed using a dental suffix, a feature undoubtedly inherited from Proto-Germanic. (Ringe, 2017) We have talked at length about the phonological processes that run through the history of Proto-Germanic and its evolution into modern Germanic languages, via Old Norse in the North. In its original, Proto-Germanic version, the dental suffix seems to have been realized (i.e. pronounced) as a voiced fricative, /ð/. (Even if the standardized Proto-Germanic spelling, among linguists, writes <d>, in Ringe for example.)

Old Norse largely preserves the realization /ð/, but the sound is, as we have patiently noted on a few examples, amply "contaminated" by the phonological environment. It devoices into a voiceless fricative, /t/, after a voiceless consonant (notably). It hardens into a voiced plosive, /d/, when it follows a nasal sound, i.e. /m/ or /n/ or the sound /l/.

Many of the phonological processes at work in the progression from Proto-Indo-European to Proto-Germanic, and on to and during the life of Old Norse, are such contaminations. Grimm's law and its successor, Verner's law, ultimately formalize some of them. Contamination - or assimilation, as grammarians such as Haugen and Spurkland would say. We shall take up and synthesize our proud findings on dental suffixes, following this time Spurkland’s lesson.

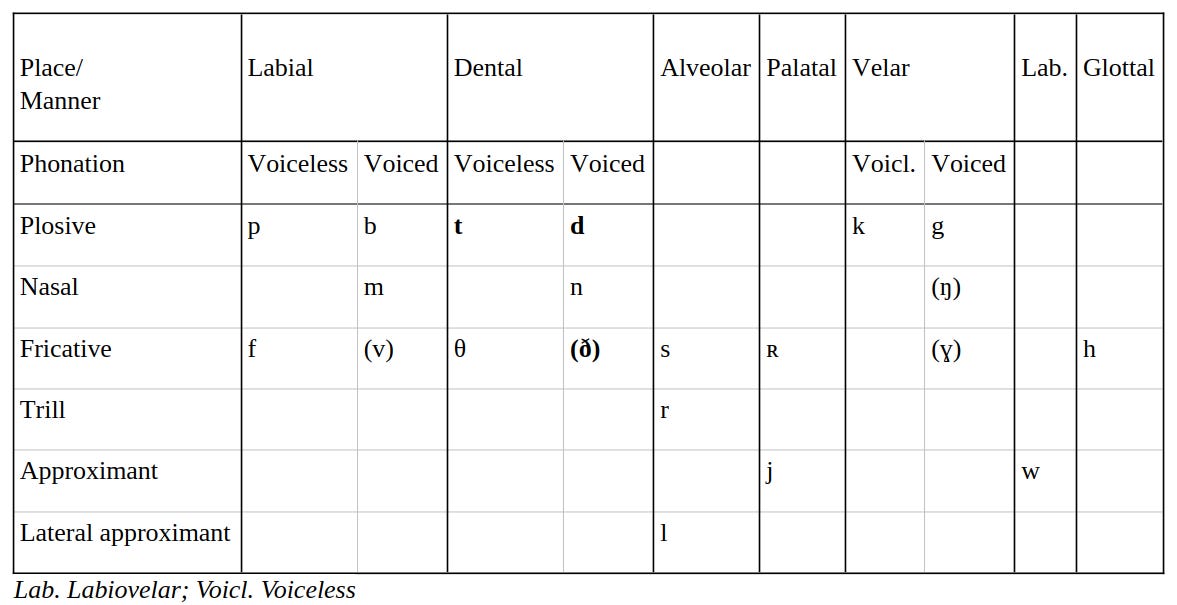

As a reminder, our phonetic table of Old Norse consonants. We highlight our dentals of interest. (In Old Norse, the sounds /d/, /t/, and /ð/ are bijectively spelled <d>, <t>, and <ð>, so we can interchangeably refer to these three letters/sounds as the sound or the letter.)

The dental suffix, Spurkland tells us, is primarily realized as /ð/ in Old Norse. (He says, apical suffix.) This is particularly the case when the weak verb is formed using a linking vowel <a>, i.e. weak verbs of the first class, also know as kasta-class.

Among the pasts we have collected earlier in The Saga of Sigurd the Crusader, Eystein and Olaf, let's choose þakka (to thank, to show gratitude) for illustration.

… ok þakkaði várum dróttni feginsamliga …

þakka is our infinitive, which coincides also the present third person plural. Let's recall our representation of weak verbs by their essential forms.

infinitive - (present indicative) - preterite indicative - (preterite subjunctive) - supinum

We then have

þakka - (þakkar) - þakkaði - (þakkaði) - þakkat

where we have highlighted the linking <a> and our voiced fricative dental suffix.

Verbs in classes two and three, namely telja-class and dǿma-class, have no linking vowel, and here assimilations come into play. (Spurkland, 1989, p.100)

det som kan skje, er assimilasjoner mellom bøyningsending and rotkonsonant

i.e., “what can occur is assimilations between inflectional ending and root consonant.”

Let's start by looking at one of our collected verbs whose root ends in a consonant, gipta (to marry, transitive or later, reflexive). We have

gipta - (giptar) - gipti - (gipti) - gipt

(Note in passing the supine gipt, very close to the Norwegian gift, married. From gipt to gift, the /p/, a voiced plosive, has turned into a voiced fricative, /f/, which closely evokes Grimm's law. The phonological laws or processes that Ringe and linguistics identify are at work across the entire Germanic spectrum, major trends that persist as the language evolves, here from Old Norse to its most modern descendant.)

The root gipt- ends with a <t>. In the past indicative, we add to the root the dental suffix and the 3rd. person singular past ending, gipt-ð-i which transforms along

gipt-ð-i →gipt-t-i (assimilation)→gipti

In the second stage, our progressive (the preceding sound influences the following sound) assimilation (a kind of contamination) takes place: the unvoiced plosive /t/ of the root transforms the /ð/ into /t/.

In the third stage, some shrinking occurs: the long (geminate) consonant, here <tt>, is shortened when preceded by a consonant. This is one of the phonological rules active in Old Norse, we shall come back to it at great length in the near future.

In addition to this rule for narrowing the double consonant, Spurkland summarizes the realization of the dental suffix in four main rules.

If the root ends in a voiced consonant, i.e. /v/ (the spelling is always <f>), /r/, /g/, /l/, /m/, /n/, the dental suffix realizes as /ð/. He gives the following examples.

kraf-ð-i, bar-ð-i, fylg-ð-i, dǿm-ð-i, val-ð-i, van-ð-i

Let's take a closer look at fylg-ð-i (illustrating the telja-class) and døm-ð-i, for example.

fylgja - (fylgir) - fylgði - (fylgði) - fylgt

dǿma - (dǿmir) - dǿmði - (dǿmði) - dǿmt

Our original dental suffix, the Proto-Germanic heir, persists in this case.

If the root ends in a voiceless consonant, the dental suffix becomes the voiceless plosive /t/. Spurkland illustrates with vak-t-i, flut-t-i, merk-t-i.

This voiceless root ending consonant can be /t/ itself as in vakta or flytja.

vak-t-i knows the evoked double consonant reduction

vakt-t-i→vak-t-i

which does not occur in flut-t-i because the geminate is not preceded by a consonant.

If the root ends in /ð/, the dental suffix realizes as /d/ and a regressive assimilation of the root /ð/ into /d/ occurs. In short, the <ðð> appearing in conjugation turns into <dd>. The phonological reason is simple: there is no such thing as a long /ð/, i.e. a /ðð/.

We had sampled, for example,

leiða - (leiðir) - leiddi - (leiddi) - leitt

hræða - (hræðir) - hræddi - (hræddi) - hrætt

where the past goes through

leið-ð-i→leið-d-i→leid-d-i

hræð-ð-i→hræd-ð-i→hræd-d-i

If the root ending /ð/ is preceded by a consonant, naturally, the shrinking further occurs. For example, virð-a does

virð-ð-i→virð-d-i (no double-ð)→vird-d-i (regressive assimilation)→vir-d-i (reduction)

If the root ends in /d/ preceded by another consonant, the dental suffix realizes as (is assimilated into) /d/. Since the geminate <dd> is preceded by a consonant, it is reduced according to the rule evoked.

Spurkland cites here

senda - (sendir) - sendi - (sendi) - sent

The contamination-reduction go as follows:

send-ð-i → send-d-i →sen-d-i

Nevertheless, those rules seem not to account for at least two of our earlier finds

stefna - (stefnir) - stefndi - (stefndi) - stefnt

sóma - (sómir) - sómdi - (sómdi) - sómt

just as Haugen's rules do not foresee val-ð-i or van-ð-i. Spurkland preempts the objection:

Nå følges ikke disse reglene helt sklavisk. Som så ofte ellers er det tale om en tendens og en tendens i utvikling.

i.e., “Now, these rules are not followed slavishly. As is so often the case, this is a trend and an evolving trend.” And spurkland cites a few more exceptions (to his own rules).

For det første kan vi finne ustemt apikalsuffiks der vi aller minst skulle vente å finne det: mæla (= snakke) - mælti, ræna (= rane) - rænti. Dessuten kan man ofte finne en veksling mellom plosiv og frikativ (dvs. [d] og [ð] etter samme konsonant: fella - (*felldi →) feldi, telja - talði; kenna (*kenndi →) kendi, venja - vandi.

In short, Spurkland's rules rob Peter to pay Paul, but linguists are well aware of the limits of any attempt at rules: languages are in constant motion. Linguistics attempts - and this is their scientific ideal - to systematize observed human facts. The question of what linguistics is in the machine age is an interesting one, and one we shall shortly enjoy wrestling with.

Finally, as some excellent Old Norse reference grammars, quoted at length in the foregoing, are by Norwegian and Nordic scholars, we hope to have convinced you a little further to convert to the beautiful Norwegian language.

References

Ringe, D. (2017). From Proto-Indo-European to Proto-Germanic (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Spurkland, T. (1989). Innføring i norrønt språk. Universitetsforlaget.