Old Norse weak verbs and dental suffix (1)

Old Norse grammar | Weak verbs | Old Norse phonology | Proto-Germanic

We recently evoked at length the coexistence, in Old Norse as well as across the Germanic languages, of weak and strong verbs. Observing the conjugation of weak German verbs, for example, we clearly noticed how the past tense and past participle of weak verbs form with a dental suffix. More precisely, we said:

What about weak verbs? Let's look briefly at the German for to cook or to love.

lieben - liebt - liebte - liebten - geliebt (to love)

kochen - kocht - kochte - kochten - gekocht (to cook)Those are German weak verbs, and as with English weak verbs, the stem vowel is not altered by conjugation. The ending -te/-ten is added to the present tense stem to form the preterite, -t to form the past participle. As in English, German weak verbs form their preterite and past participle by means of a dental suffix, that is to say, some /t/ or /d/ sound or similar: this, anew, dates back to Proto-Germanic times.

We shall come back to this Proto-Germanic origin in a moment, but for now, let's take a look at Old Norse's realization of this dental suffix, we said, some /t/ or /d/ sound or similar.

For example, let us examine a passage from Heimskringla, The Saga of Sigurd the Crusader, Eystein and Olaf, where Chapter 23 appears rich in weak verbs in their preterite form or past participle.

Ólafr konungr tók sótt, þá er hann leiddi til bana; ok er hann jarðaðr at Kristskirkju í Niðarósi; ok var hann hit mesta harmaðr. Síðan réðu þeir tveir konungar landi, Eysteinn ok Sigurðr, en áðr hǫfðu þeir þrír brœðr verit konungar 12 vetr, 5 síðan er Sigurðr kom til lands, en 7 áðr. Ólafr konungr var 17 vetra, er hann andaðist, en þat var 9 Kalendas Januarii.

The dental suffix realizes as <d> in leiddi, and <ð> in jarðaðr, harmaðr, hǫfðu, andaðist. Let's collect other examples from the same saga.

… en eptir dvaldist mikill fjöldi Norðmanna …

… Þá mælti Sigurðr konungr …

… ok tók þá bók hina dýru, er hann hafði haft í land …

… ok var þessi leiðangr kallaðr Kalmarna leiðangr …

… ok lagði hann þar mikit fé til …

… ok þakkaði várum dróttni feginsamliga …

… Þrimr vetrum síðar en krosskirkja var vígð …

… ok hræddist bæði sult ok píslir …

… Þá stefndi Sigurðr konungr máli þessu til Arnarnesþings …

… en þeim öllum viltist sýnin …

… hann gipti eina dóttur sína Heinreki keisara …

… heimti hann Ívarr til máls við sik …

… en þann veg skipti þá til, sem …

… var þat sagt, at …

… ok gerðist þá ilt til matar …

… Þá er Sigurðr konungr sigldi fyrir Spán …

… meðan hann lifði …

… sem honum sómdi at veita ríkum mǫnnum …

We are now witness to three realizations of the suffix dental, which anew forms in the highlighted examples either the preterite or the past participle. Namely, we find a dental suffix realized as

<d> in dvaldist, hræddist, stefndi, sigldi, sómdi,

<t> in mælti, haft, viltist, gipti, heimti, skipti, sagt,

<ð> in hafði, kallaðr, lagði, þakkaði, vígð, gerðist, lifði

Can we draw a model from these observations, i.e. can we predict from the infinitive form whether the dental suffix of the preterite (and past participle) will be <d>, <t> or <ð>?

A twin question from a historical perspective: what historical factors determine which form of the dental suffix appeared in Old Norse weak verbs? Note the important difference. Both questions seek to explain the realization of the dental suffix as <d>, <t> or <ð>. However, the first is synchronic, i.e. it looks for explanations within the fixed temporal framework that corresponds to Old Norse. The second is diachronic, and examines the evolution of languages from Proto-Germanic to Old Norse, via Proto-Norse and their close relatives. Of course, knowing how the observed phenomenon derives historically paves the way for a synchronous explanation. (This duality of synchronic and diachronic research is captivating, and we shall devote future reflections to it.)

But first, back to our synchronic observation. Typically, the phonological environment influences orthography. Here, we notice promptly that, in all our examples above, the dental suffix is realized as <ð> after a vowel: kallaðr, þakkaði, jarðaðr, harmaðr, hǫfðu, andaðist. With consonants, the findings are less obvious. We can indeed collect, regarding the preterite forms,

<l> (dvaldist, sigldi), <n> (stefndi), <d> (hræddist, leiddi), <m> (sómdi) before <d>

<l> (mælti, viltist), <p> (gipti, skipti), <m> (heimti) before <t>

<f> (hafði, lifði), <g> (lagði), <r> (gerðist) before <ð>

and regarding the past participles

<f> (haft), <g> (sagt) before <t>

<g> (vígð) before <ð>

Ideally, we would like to conclude something like: the realization of the dental suffix after a consonant depends on the "consonant type". And for that, we need to say a brief word at least about Old Norse consonants.

Phonetics distinguishes consonants by certain phonetic characteristics, the most important of which are

Manner of articulation, e.g. stops, fricatives and nasals;

Place of articulation, i.e. where in the vocal tract the consonant is obstructed, and which speech organs are involved, for instance, a bilabial (both lips), alveolar (tongue against gum ridge) or velar (tongue against soft palate) articulation;

Phonation, i.e. whether the vocal cords vibrate during articulation (“voiced”) or not (“voiceless”).

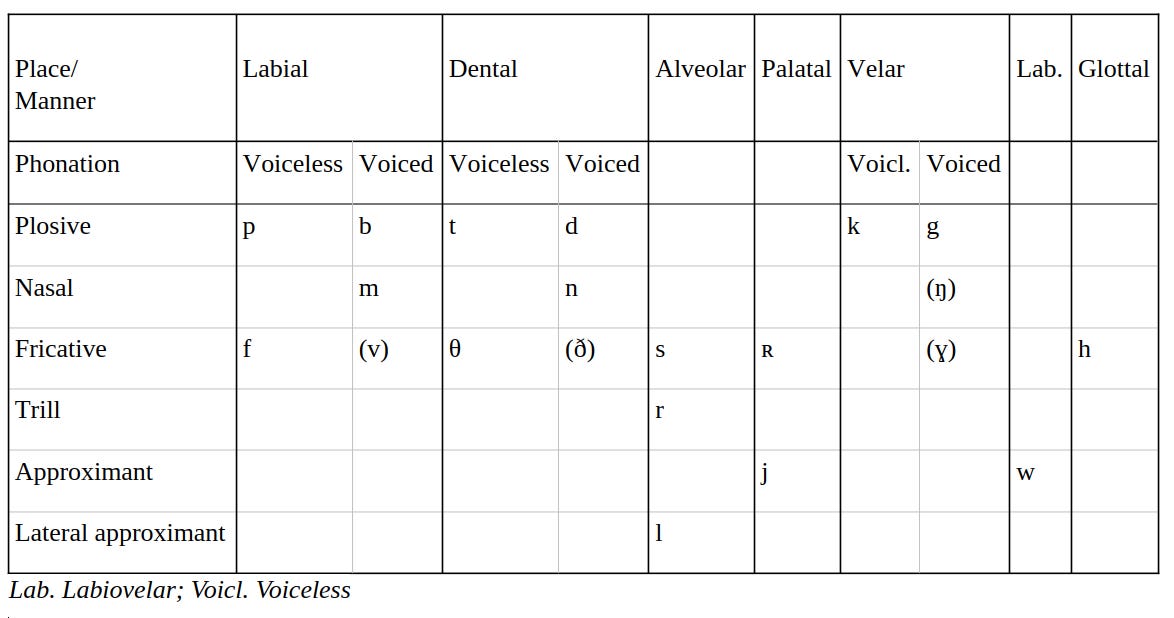

Along the lines of this typology, Old Norse consonants are arranged as follows.

(We follow here closely Wikipedia, Old Norse, Consonants, and the description is similar in Haugen.) (Haugen, 2015, p. 21)

A word about notations. Up to now, we have noted between brackets <>, the grapheme, i.e. the letter as written. In the preceding phonology table, these are not graphemes, but phonemes, sounds, usually noted between slashes //. The correspondence is not totally bijective. For example, the letter <g> can be realized by the phonemes /g/, /ŋ/ or /ɣ/, depending on the phonological context. In the table, the phonemes in (parentheses) have no corresponding grapheme, this is also the case for /θ/ and /ð/, both phonemes being rendered as <θ> in standardized spelling. Let's note in passing that when the grapheme-phoneme correspondence is unique, the /sound/ and the <letter> are unambiguously equivalent. Back to our consonants.

We won't describe the whole system today, just take a closer look at the consonants we have collected.

Before the dental suffix /d/ we find /l/, /n/, /m/, all of which are voiced (/l/ can be both).

Before /t/, we find the voiceless consonants /r/, /l/, /p/. (We can note an obvious exception heimti, /m/ being voiced.)

And all phonetic realizations of <g> as well as /r/, found before /ð/, are voiced. <f> in hafði or lifði is realized as /v/ which is voiced too.

These are great finds! In short, the dental suffix, in the formation of the past tense and past participle of weak verbs, is realized in

/t/ (voiceless) after a voiceless consonant;

/d/ (voiced) after /m/, /n/ or /l/, three consonants that are a little special to Old Norse, as they classify, just like vowels, as sonorants;

/ð/ (voiced) after a vowel (this linking vowel a of the first class of weak verbs) or after a voiced consonant.

The voiced or voiceless character of the dental suffix seems to arise through contamination. A kind of proximity rule emerges, which we could now try to trace diachronically.

Let's return to the phenomenon's proto-Germanic ancestry, which explains its dissemination across the Germanic spectrum. That's what we said in our epic of Old Norse weak and strong verbs.

What characterizes all weak verbs, Ringe tells us, is the common formation of the past participle, of a default finite past tense (all tenses, modes and persons), with the exception of a distinct singular indicative past tense. More specifically, the past participle of weak verbs always has a stem vowel *-a- or *-ō-, and is formed with the suffix *-da- (with a few exceptions). The past tense suffix begins with the dental obstruent *-d-, with the suffix and endings following a well-defined pattern. (Ringe, 2017, p.280) (To level out the terminology, a conjugated verb is formed by a stem, a suffix (here, the past tense suffix begins with a *-d-) and an ending typical of the mode, tense and person.)

First of all, the dental suffix is already present in Proto-Germanic, that most recent ancestor - reconstructed by linguistics - common to all subsequent Germanic languages. Although classically spelled <d>, it seems to be have been pronounced as the voiced fricative /ð/. It would have hardened to the plosive /d/ in the West-Germanic languages while remaining a fricative in the North-Germanic branch, including Old Norse.

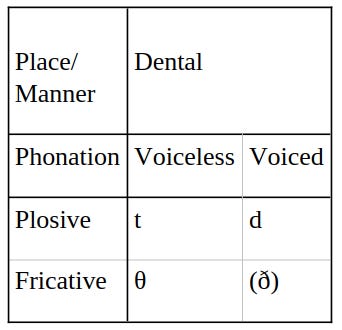

Here is anew (the relevant extract from) our phonetic table.

The Icelandic case corroborates our hypothesis of contamination by context. Gobiirsch, although presenting a later Icelandic phonological phenomenon in his article, tells us (Gobiirsch, 2021)

While NWGm b, d, g are phonologically voiceless, they may be partially or fully voiced medially in a voiced environment.

In Old Icelandic, obstruents get voiced and devoiced based on their phonological environment.

There may also be voicing of the NWGm fricatives medially in a voiced environment. As in all northern North-West Germanic (Old Norse, Old English, and Old Saxon), there was only one series of fricatives with complementary distribution of voiced and voiceless variants in Old Icelandic. The loss of voicing contrast in fricatives present in Common Germanic was due to the final devoicing of Gmc β, ð, γ and the voicing of Gmc f, θ, x medially in a voiced environment (cf. Goblirsch 1999b).

Old Icelandic, like Old Norse, devoices the dental suffix /d/ in /t/ after a voiceless consonant, and in some other cases (heimti, found in the same way in modern Icelandic, may be one of those).

In fact, the phonological reciprocal influence of the suffix dental on its surroundings is plausible, if we read Ringe carefully:

Immediately before *t, all labial consonants were replaced by *f and all dorsal consonants by *h. This can be seen in inflectional forms such as past singular *gaft 'you gave' (compare Gothic and Old Norse gaft, from *gebaną 'to give') and present singular *maht 'you can' (compare Old English meaht, Old High German maht, from *maganą 'to be able').

He speaks here of Proto-Germanic transformation. (Ringe, 2017, p.247) A number of regular transformations transform language over the generations, from Proto-Indo-European to Proto-Germanic, then on towards modern languages. One of the most important of these laws is Grimm's Law, named after the famous 17th-century philologist of Germanic languages and writer. Grimm’s law, tells us Ringe, can be seen as a “chain shift” where the component sound change together. It consists, thus, of several sound changes, that are active in the transition from Proto-Indo-European to Proto-Germanic. By the most significant of them,

PIE voiceless stops became PGmc fricatives, provided that they were not immediately preceded by another obstruent (usually *s, but sometimes another stop).

(Ringe, 2017, p.113-122)

This might well justify our dental suffix rendered as the fricative /ð/, at the Proto-Germanic level. Ringe doesn't specify this precise case, and exact genealogy is not possible in such a short space. But we do appreciate the overall historical movement.

We shall be coming back to Grimm's law, its successor (in the sense that the variations it describes occur, historically, after Grimm's chain shift), Verner's law, and, naturally, the morphology and phonology of Old Norse.

References

The Saga of Sigurd the Crusader, Eystein and Olaf. In Heimskringla III. In B. Aðalbjarnarson (Ed.). (1941-51). Íslenzk fornrit (Vol. 28). Hið íslenzka fornritafélag.

Wikipedia, Old Norse, Consonants, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Old_Norse#Consonants

Haugen, O. E. (2015). Norrøn grammatikk i hovuddrag. Novus.

Ringe, D. (2017). From Proto-Indo-European to Proto-Germanic (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Goblirsch, K. G. (2001). The Icelandic consonant shift in its Germanic context. Arkiv för nordisk filologi, 116, 117-133.