Reading Íslendingabók (1)

Norse practice | Íslendingabók | Chapter I. The settlement of Iceland

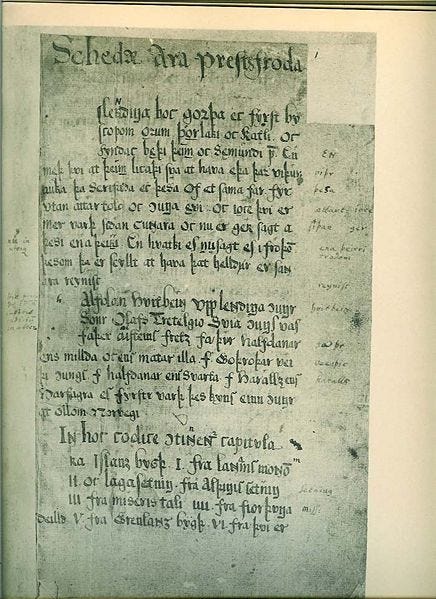

The Norse practice series takes you through the practice of extensive reading. You practice reading and translating a lengthy piece of text, longer than those in the Grammar by sagas series. In the Grammar by sagas series, for example here or there, we draw on small texts from the sagas to infer together elements of Old Norse grammar. In the present Norse practice series, we read a longer text where we practice finding the translation anew, piece by piece: sentence by sentence, clause by clause, phrase by phrase. Of course, we also dive into the world of sagas, here in Íslendingabók, whose authorship is assuredly attributed to Are Torgilsson Frode. The Saga chronicles series will take a close look at the veritable treasure hunt involved in tracing the authorship of sagas, and in particular at the philological history of the Íslendingabók, not only one of the most famous texts in Old Norse literature, but also a rich source of clues for establishing the authorship of other works.

As this is our first “lesson” in extensive reading, we shall give special attention to the method. Typically, pedagogues of linguistics, eager for seriousness and to adequately typologize everything, define extensive reading as the exercise that seeks a context-based general understanding of the text under study, more than complete comprehension and detailed analysis: in short, a focus on quantity and fluency. We have our own reading of extensive reading, and this exercise illustrates our approach. It cannot be ruled out that, over time, we further refine and improve on how we proceed.

We will read and examine the beginning of the first chapter, entitled Frá Íslands byggð, which can be translated as About the settlement of Iceland.

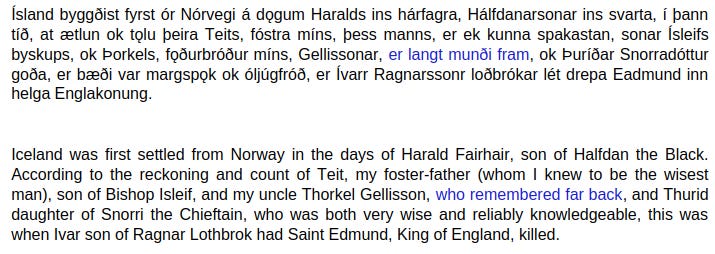

This is the very first paragraph, our first "long" text, and its English translation. Reading the translation is allowed at this stage, we shall see what our Icelandic saga is actually about.

Ísland byggðist fyrst ór Nórvegi á dǫgum Haralds ins hárfagra, Hálfdanarsonar ins svarta, í þann tíð, at ætlun ok tǫlu þeira Teits, fóstra míns, þess manns, er ek kunna spakastan, sonar Ísleifs byskups, ok Þorkels, fǫðurbróður míns, Gellissonar, er langt munði fram, ok Þuríðar Snorradóttur goða, er bæði var margspǫk ok óljúgfróð, er Ívarr Ragnarssonr loðbrókar lét drepa Eadmund inn helga Englakonung. En þat var átta hundruð ok sjau tigum vetra eftir burð Krists, at því er ritit er í sǫgu hans.

Iceland was first settled from Norway in the days of Harald Fairhair, son of Halfdan the Black. According to the reckoning and count of Teit, my foster-father (whom I knew to be the wisest man), son of Bishop Isleif, and my uncle Thorkel Gellisson, who remembered far back, and Thurid daughter of Snorri the Chieftain, who was both very wise and reliably knowledgeable, this was when Ivar son of Ragnar Lothbrok had Saint Edmund, King of England, killed. That was eight hundred and seventy winters after the birth of Christ, as it is written in his saga.

We learn more about the historical background to the first settlement of Iceland by Norwegians. The author evokes his sources, who are also his famous ancestors.

The Old Norse has only two sentences, the first is very long, and this is our first working material. It ends with some considerations about a certain Eadmund inn helga Englakonung. So, we can see that the English translation corresponding to this first long sentence stops on the considerations on Saint Edmund, King of England, who was killed.

So we start at the beginning and try to map the first Old Norse proposition, highlighted in blue, with its English equivalent.

How do we know when we have a proposition? A little experience tells us. More precisely, we quickly identify byggðist as a verb (see Grammar by sagas here). We glance at the surrounding words, in the highlighted section, and find no other finite verbs. The immediate continuation, í þann tíð, introduces some indication of time, while at seems to us to be a preposition, inserting an adjunct of some kind. A typical Old Norse proposition will have a subject, a verb and a object. As we explained earlier, despite the possible debate among linguists, the structure subject, verb, object, in this order, has a high probability. But it is not the only possible one. The sophisticated inflectional system dispenses with strict word order. There are also a number of situations in which the subject, verb or object is elided; impersonal constructions; and short sentences in which the verb is in infinitive form. The grammarian Haugen calls these "situations" reformulations: the original "normal" proposition - subject, verb, object - has been reformulated respectively into a proposition whose subject, verb or object is elided, or into an impersonal proposition, or into a short infinitive phrase. (Haugen, 2015)

The association with English is made particularly simple by the abundance of proper nouns, e.g. Nórvegi for Norway, the similarity in word order, and of course, similarities in form, e.g. fyrst for first, dǫgum for days.

The rest of the identification process is far less straightforward. Let’s turn back to our probable indication of time.

The noun tíð is no mystery, a little imagination speaks for at that time. Now, the very first time the notion of time is expressed in the English equivalent, is with when:

A whole story of sources and ancestors is interspersed, whose correspondence with the English can be guessed thanks to the anchors provided by proper names.

We also note the similarity of the relative clauses: the Old Norse one is introduced by er. Knowing that ok is the coordinating conjunction and helps, of course.

The incise clause can therefore be delimited,

which leaves the piece that interests us now, expressing this when.

Here too, er introduces a relative proposition. In this time, when or as it rendered here, this was when. So, when what? When Ivar son of Ragnar Lothbrok had Saint Edmund, King of England, killed.

An attentive mind may object that the time adjunct formed by what has just been underlined in blue belongs to the first proposition, the main one, and that the relative proposition when Ivar son of Ragnar Lothbrok had Saint Edmund, King of England, killed is enshrined in this main one. This is a very valid opinion. In this reading, the main Old Norse proposition covers at least what is highlighted in blue in the following

and as we shall see in a moment that the central incise is a vast adjunct (of manner), it actually extends to the entire piece quoted. For our progressive breakdown, which seeks to understand Old Norse-English matches, we do need to draw subsets, as we have done. A first, main position, which could function independently. Its time adjunct, which contains a relative proposition, and now, the big incise starting with the preposition at.

We have already spotted the final relative proposition, in which the author panders to his ancestors, both margspǫk and óljúgfróð. We can spot another one easily, as it begins here too with the subordinating conjunction er.

And a third, for the same reason.

The rest of the Old Norse incise is clearly comparable to the English, full of proper nouns, and without technical difficulties.

We take a breath of fresh air, and resume with the beginning of our very long proposition (or, if you prefer, with our independent proposition, the one that has been stripped of its furthest adjuncts).

Everything revolves around the verb: the subject Ísland, the place adjunct (expressing provenance) ór Nórvegi, the time adjunct fyrst, the time adjunct á dǫgum Haralds ins hárfagra. Here, even more precisely, we have the correspondance

and then that of the genitives, the noun complements

The genitives are themselves completed by an apposition, Hálfdanarsonar ins svarta, of Harald Fairhair, which is also in the genitive.

Now you have the gist.

With these Russian doll-like associations of word groups, we have tried to retrace what might be going on in the mind of an extensive reader. It is less a question of reading "without fully understanding", that is to say, skimming, than of methodically finding the translation anew - a historical translation right in front of your eyes, the one obtained with a modern generative A.I. tool, or the one you have in mind because you are familiar with the passage.

Ísland byggðist fyrst ór Nórvegi á dǫgum Haralds ins hárfagra, Hálfdanarsonar ins svarta, í þann tíð, at ætlun ok tǫlu þeira Teits, fóstra míns, þess manns, er ek kunna spakastan, sonar Ísleifs byskups, ok Þorkels, fǫðurbróður míns, Gellissonar, er langt munði fram, ok Þuríðar Snorradóttur goða, er bæði var margspǫk ok óljúgfróð, er Ívarr Ragnarssonr loðbrókar lét drepa Eadmund inn helga Englakonung.

Reread the old Norse patiently, and note, probably, that you "understand". What understanding means, is probably: knowing how to decompose quite precisely, and each piece, matching it to something you already know.

And to conclude the opening paragraph of the first chapter of Íslendingabók, read, likewise, the second sentence:

En þat var átta hundruð ok sjau tigum vetra eftir burð Krists, at því er ritit er í sǫgu hans.

parallel to its translation:

That was eight hundred and seventy winters after the birth of Christ, as it is written in his saga.

sǫgu is indeed saga. The circumstances of this vowel change, from a to the ǫ-vowel, also called o with ogoneko, or o caudata, will be the subject of much comment later.

Here, for saga and far north enthusiasts, the second paragraph of the first chapter of Íslendingabók, to be read in closer details later.

A Norse man named Ingolf is truthfully said to have gone first from there to Iceland, when Harald Fairhair was sixteen winters old, and for a second time a few winters later. He settled in the south at Reykjavik. Ingolf's Headland is the name given east of Minthak's Eyr, where he first came ashore, and Ingolf's Mountain west of Olfossa River is where he later claimed his property

References

Haugen, O. E. (2015). Norrøn grammatikk i hovuddrag. Novus.