Future and movement (2)

Intermingling | Comparative grammar | Grammaticalization | Future tense

Language is in motion: each new statement, written or spoken, confirms, extends or ruptures existing forms. If the dissonance is too marked, there is a fault of taste or grammar. If the contravention is acceptable, there is innovation, the option of a new way of saying, which usage may or may not endorse. In particular, abstract notions seek expression. Speakers experiment with the concrete language that the present makes available to them: they try to evoke the abstract metaphorically. Eventually, expressions formalize, and enter grammar.

Theorists call grammaticalization the linguistic process that gradually metamorphoses lexical items into grammatical ones. We have recently, by way of illustration, visited modal verbs from Old to Modern English, and evoked the frequent intermingling of the expression of tense and modality. The future tense auxiliary will, in particular, bears also modal nuances. It has been grammaticalized as a future tense marker by analogy with its predecessor's lexical meaning - intention and willingness.

Another typical pathway in the grammaticalization of the future tense originates from verbs of movement. This is what we shall be looking at more closely - in the present essay, we will evoke the phenomenon across several languages, especially of the Germanic spectrum, and this will lead us in an upcoming part three to a study of the future tense in Old Norse.

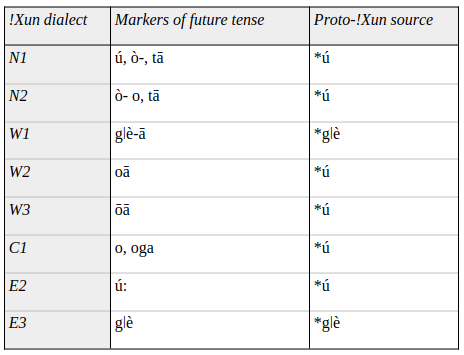

Reconstructing a Proto-!Xun, a hypothetical ancestor of the !Xun language spoken by hunter-gatherers in south-west Africa, no trace of “a conventionalized future tense form or construction” can be found, Heine and his co-authors tell us. (Heine, Kuteva & Narrog, 2017, p.4-9) In contrast, Proto-!Xun seems to have featured the verbs of motion *ú (go) and *gǀè (come), whose descendants participate to the formation of the future tense in today's !Xun dialects. Most probably, Heine concludes, these verbs preexisted the grammatical markers of the future tense in the history of the !Xun, and the latter derived from the former: “movement-based future tenses” developed. The following is a repertoire of !Xun dialects and their future tense markers.

W1 and E3 clearly developed their markers from the Proto-!Xun *gǀè (come). N1, N2, C1, E2, perhaps W2 and W3, from *ú (go). We also find the conjunctions tā and oga, which will soon prove pivotal in the discussion. In addition, the !Xun dialects can draw on three types of constructions to form the future tense. These differ in the type of association between the two verbs - auxiliary and lexical - that they involve. A closer look at these three types of construction reveals much about the ongoing process of grammaticalization, from verbs of movement to future tense markers. We find indeed

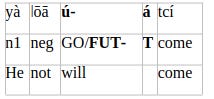

A complement-based future where the suffix -á serves to augment the valency of the verb, that is, its aptitude to take on a complement, e.g. turning an intransitive verb into a transitive one. Here is an example from the N1 dialect, with Heine’s encoding. (T refers to preposition/suffix, FUT to future marker, TOP to topic marker)

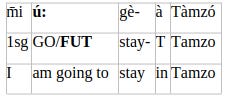

A serializing future that juxtaposes both verbs, here in the E2 dialect

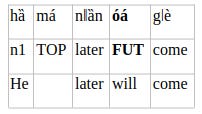

A particle-based future where future markers bear resemblance with but differ from gǀè / ú. Namely we can find oga, ò-tā, óá, forms that are undergoing phonetic, syntactic, morphological coalescence. In the following W2 example

the future marker óá results (most probably, Heine says) from *ú-ā > *ó-á > óá where -á is the above (1) complement-friendly suffix. Similarly, ò-tā and oga can certainly be reconstructed back to a coalescence of *ú with the conjunctions tà and kà respectively.

Here comes the most interesting part. Our suffix -á and conjunctions tà/kà are not limited to forming the future tense. -á adapts, in general, a verb to take on a complement. This can be a verb in the past tense (past tense marked by kè), as in (W2)

hȁ má kè ú- á ḿ. (He went to eat.)

Likewise, tà and kà serve coordination in general, as in (W2)

hȁ má kè ú kā m̋. (He went and ate.)

Consequently, we can assume future tense constructions to still be semantically colored by their lexical counterparts, coexisting in the dialects. For instance, considering (N1)

m̄ txòm, à ò-tā ǁé (My uncle, you are going to die)

the grammatical (future tense) marker ò-tā ǁé (are going to die) is in the process of getting abstracted from a lexical (literal) ú tā ǁé (go and die). Perhaps a little of the literal “go and die” remains in the abstract, future expressing “will die”. It is nevertheless difficult to assess the degree of semantic bleaching. It might be assumed to be proportionate to the coalescence degree, ò-tā being closer to (and thereby potentially more evocative of) the literal form ú tā it derives from than oga is to its putative parent ú kā. (In other words, the latter can be deemed more coalesced than the former, thereby giving less away of its origins.) Yet, isn't present-day English completely insensitive to the literal motion meaning when using be going to as a future marker - while the motion verb (going) is perfectly visible, with no erosion or truncation?

Ultimately, we observe a certain disparity in the morphosyntactic paths followed in the different dialects of !Xun by the development of the grammatical future, and (perhaps) in the degree of its advancement; we can also observe a unanimous convergence of the semantic path: it is systematically a primitive verb of motion, *ú or *gǀè, from which the expression of the future, whatever its form and syntax, derives. Since the youngest (reconstructed) common ancestor has no future marker, this latter similarity cannot be inherited. Heine then formulates the hypothesis of a great tendency, whereby the semantic shift precedes and drives the morphological/syntactic transition -“structural change lags behind semantic change.” (Heine, Kuteva & Narrog, 2017, p.23)

Heine is a specialist in African languages, and the comparative study of their respective dialects is extremely instructive. As it were, dialects synchronize diachrony, bearing witness at the present time to several stages in a similar ongoing process.

Many synchronic differences between dialects can in fact be interpreted as reflecting differing stages or ways of grammaticalization. (Heine & Reh, 1984, p.91)

However, a certain degree of their interdependence cannot be excluded. As well as reciprocal influences through language contact, something - features or tendencies at work - inherent in the inherited linguistic system could explain the similarity of grammaticalization processes originating after divergence from the shared ancestor. (Heine concedes the hypothesis of an inherited shared drift while the process referred to remains nebulous.)

Here, cross-language studies substantiate the demonstration. Staying in Africa, verbs of motion (together with verbs of volition, we remember the English modal auxiliary will) are the most frequent sources of future markers.

The Nilotic dialects Acholi and Lango resort to a periphrastic construction where bino (to come) is followed by a verbal infinitive form.

Here again, the dialectal comparison freezes unequal degrees of advancement of a (same kind of) grammaticalization. I will eat is an a-bino cammo in Lango and an a-bi-camo in Acholi, the latter having (probably) further coalesced *an a-bino camo into *an a-bino-camo (affixation), later eroded into an a-bi-camo.

Standard Ewe marks the future by prefixing verbs with á- from the verb vá- (to come).

Some Kru languages use a derivative of either come or go.

Duala, a Bantu language, uses derivatives of both to nuance future expression.

Ultimately, the languages just mentioned share with !Xun the same “channels of grammaticalization” - not only the same semantic source, but also the same types of constructions - a complement-based (or particle-based, both differing perhaps only, as we observed, in the degree of coalescence/grammaticalization) and a serializing futures - while a secondary, periphrastic adverbial construction is also observed. (Heine & Reh, 1984, p.131-132) Although contact influences are acknowledged, the respective geographies of the Nilo-Saharan (Nilotic), Niger-Congo (Kru and Bantu) and Kx'a (!Xun) families of languages are mostly disjointed. A genetic explanation for the similitude is also discarded.

But the distance is even greater with Indo-European languages, where the same great tendency can be observed. We remarked earlier on the English be going to. From this entry point, we shall now turn our attention to Germanic cases of grammaticalization of the future tense from verbs of motion.

African dialects, as we have just noted, offer a snapshot of grammaticalization in progress. As we recall, we can suspect semantic bleaching not to be fully realized in the !Xun (N1)

m̄ txòm, à ò-tā ǁé (my uncle, you are going to die)

where the future tense marker ò-tā (are going to) still bears the form and phonetic of ú tā ǁé (go and die) - and might thereby be evocative of the former.

It is reasonable to assume a similar ambiguity - between motion and future interpretations - for the English be going to + infinitive - an ambiguity that lessens as the phrase enters grammar. (Heine, Kuteva & Narrog, 2017, p.23) Let's observe a passage in 15th-century English (1477, Mubasshir ibn Fatik, Dictes or sayengis of the philosophhres; in Traugott, 2012)

ther passed a theef byfore Alexandre that was goying to be hanged whiche saide …

(a thief who was going to be hanged passed before Alexander and said …)

Here, we visualize clearly the thief literally passing by Alexander on his way to the gallows. But the exact same phrase can also be experienced in a modern way, as an expression of the future stripped of all evocation of motion.

The following passages trace the gradual emergence of the construction in The Penn-Helsinki Parsed Corpus of Early Modern English. Throughout the first half of the 17th century, be going to is mostly followed by a place name, and fewer than ten occurrences by an infinite verb. In the very first we encounter (1599)

Sir, the Germane desires to haue three of your horses : the Duke himselfe will be to morrow at Court, and they are going to meet him.

the preceding clause indicates the place (at the Court) and time (to morrow) of future action (meet him): this action is both “meet” (in the future) and “going (to that place)”. Interestingly, the interpretation can be wholly that of motion without loss of the future tense: to morrow already bears it. In this early instance, be going to + infinitive is a redundant future tense carrier.

Next, a passage by Shakespeare, in the “buck-basket scene” from The Merry Wives of Windsor (1599), catches our attention. (The merry wives trick Falstaff into hiding in the basket, which their servants then carry to dump into the Thames.)

Looke, heere is a basket, if he be of any reasonable stature, he may creepe in heere, and throw fowle linnen vpon him, as if it were going to bucking

A rare occurrence followed by a gerund, which can be interpreted as a place (the place of bucking) or an activity (the process of being bucked, with fowle linnen (foul laundry) as the passive subject).

Just like above, in the following (1647-1648)

It is now about 12 of the clock, Mooneday noone and my Cozin Dalison is going to take water for Gravesend. Shee will bee at Deane Tuesday night.

Mooneday noone already bears the temporal reference, making is going to (take) potentially redundant as a future marker.

In a late 17th century instance (1696)

The greatness of your Necessities, Tam, is the worst Argument in the World for your being patiently heard. I do believe you are going to make me a very good Speech, but

the context involves no indication of place and time, and abstraction to a mere future tense marker has clearly taken off.

What drives language change? What force causes lexical items to shift to grammatical ones? It is usage, it seems, that secretes grammar.

… [interlocutors] constantly propose new discourse options, and some of these new options may be used regularly and give rise to new patterns of grammar.

(Heine, Kuteva & Narrog, 2017, p.23)

Source selection - verbs of motion, for English will, as we have seen, intention - is governed by semantic implication. In to go (to) or to come (to) space and time fuse. Both imply an action that unfolds in the future, namely, until (time) arrival where (place) the verbal complement points to. In short, the scenario might be as follows. A language originally lacks a stable, unambiguous means of expressing some abstract notion - perhaps interlocutors are often forced into periphrases, misunderstood, or asked to repeat. They unconsciously take advantage of a semantic bridge, which usage formalizes. A space-time metaphor.

Once grammaticalization is complete, the frequency of occurrence in the corpus increases. Analysis of discrete samples is no longer adequate to capture patterns. Hilpert (2008) proposes a quantitative study of the Germanic future: he scans corpora for collexemes of future-expressing constructions, the lexical items they statistically attract most. (Co-occurrence frequencies are corrected for total corpus frequencies.)

In the British national Corpus (late 20th century), depend, know, remain and become rank among the top collexemes of will, while be going to strongly attracts do, get, say, put or kill. (Hilpert, 2008, p.40-41) The latter clearly involve an intentional and voluntary agent who has control over an action (agentiveness), and they require or likely come with a direct object (transitivity). In contrast, the former are non-agentive. Arithmetic confirms that the two constructions expressing the future have distinct semantic preferences, which raises questions about their interchangeability. Why does is going to attract agentive, imperfective and transitive verbs? Hilpert's statistics also tell us about the paths of grammaticalization.

Bybee and Pagliuca (1987) confirm the polysemy, in many languages, of future markers. Unsurprisingly, modal nuances abound among the additional meanings. Future tense is a very special tense indeed. Unlike past and present tenses, it concerns what has not yet taken place: realization, at the time of utterance, is no more than a possibility - backed up by a desire, an intention, an obligation, a strong probability. The semantic halo of a future tense marker, the authors recognize, is linked to the meanings of its lexical source. Old English sċeal was primarily used for commands and modern shall still denotes obligation while will is historically desire-based; movement-based futures, for their part, carry less nuances of modality. The authors further suggest that there exist a typical, four-stage semantic progression that holds across languages. Hilpert account for the model as follows:

Obligation, desire, ability, come, go

Intention, root-possibility, immediate future

Future

Probability, possibility, imperative, use in complements

It makes two notable hypotheses. First, both modality-based and movement-based futures develop necessarily through an early stage where intention is expressed. (This may not be clear from the outline above, where the second stage seems to present several semantic options including intention, but Hilpert makes otherwise explicit that this has been posited by Bybee and Pagliuca.) Second, future marking and expression are not the term of semantic development. The grammaticalized future marker is the source from which other meanings develop. (Hilpert, 2008, 24-27)

Hilpert puts this model to the test by systematically studying the collexemes of three movement-based future tense marker, Dutch gaan, English be going to and Swedish komma att. (Hilpert, 2008, p.113-122; p.126-131)

While modern be going to, as we have mentioned, is found to attract “verbs that are transitive, punctual, and highly agentive”, verbal complements to modern gaan are most often “intransitive, temporally extended, and non-agentive”. Diachronic corpus studies “suggest that these differences are not due to recent semantic changes”: despite similarities in the broad outlines, the details of their semantic paths differ.

Dutch, like English, readily expresses the future with the present tense, but also features two specific periphrastic constructions: resorting to the auxiliaries zullen and gaan. zullen is a temporal auxiliary: of the future (will, is going to) when conjugated in the present tense, of the conditional (would) when conjugated in the past tense. But it is also a modal auxiliary, with nuances of possibility, probability, moral obligation (probably then closest rendered by the German sollen). The different shades are difficult to disentangle in

Nou, verbeter je maar in het vervolg. Morgen zullen we je wel helpen.

(Well, improve yourself in the future. Tomorrow we will (be there to / be able to / be glad to) help you.)

(Louis Couperus, Noodlot, 1918)

Here, zullen clearly works as a future auxiliary, underpinned by the time adjunct tomorrow, but the context (the addressee is invited to improve, he can still be helped tomorrow, but this may be the last time, and the adverb wel bears a potential hue of likelihood) reawaken the modal flavors.

A modern grammar will endorse gaan (to go) as a future auxiliary

when the agent literally is moving to a place to perform an action,

more generally, to indicate any kind of intention or plan to perform the action, or

to indicate the start of an action in the future. Het gaat zo hard regenen. (It is going to rain / start raining. [It doesn’t rain yet])

and deplore that, in practice, the use of gaan is stepping on zullen's toes.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, verbs of movement and posture are the ones most frequently attracted by gaan. (Hilpert, 2008, p.116)

Nu willic gaan lopen al in mijn huus. (Now I want to go home.)

Daer gaet hij strijcken! (There he’s running off"!)

Besides lopen (walk), strijken (run off), reizen (travel), liggen (lie), treden (step), verhuizen (move), we also find some activity verbs such as preken (preach) or stellen (put). We can note the preeminence of agentiveness, intention, and atelicity (lack of a specific end point). (To preach (preken) is intentional, accomplished by an agent, and continues as long as the action occurs. In contrast, to pronounce is telic - it requires something to be pronounced - a speech -, and concludes by the end of it.)

Second-period verbs, in the 18th and 19th century extend their span to telic verbs such as opzoeken (find), onderzoeken (analyze), vertellen (tell), geven (give) or nemen (take); intention and agentiveness fade, as for instance gaan sterven (die) joins the top collexemes.

Uilenspiegel zeide tot Nele: -Liefste nu gaan we sterven. (Uilenspiegel said to Nele: -Darling, now we’re going to die.)

The trend extends into modern times, with the notable attraction of cognition and emotion verbs: beminnen (love), voelen (feel), twijfelen (doubt). The latter are low in agentiveness and intention, as the following example clearly shows.

en daardoor gaat ge twijfelen aan het echt-yijn dier (and that makes you doubt the reality of that benevolence)

Whereas gaan has a clear preference for verbs of movement and posture, be going to particularly attracts speech act verbs. Such preferences, Hilpert postulate, drive semantic development. “Verbs such as answer or begin are perfective, and thus prefigure the modern tendency of be going to to express punctual, telic events.” Like gaan, be going to begins (1710-1780) by attracting verbs high in intention and agentiveness: say, fight, give, make. Unintentional, non-agentive future events make their appearance in a second period (1780-1850).

In the true sleepy tone of a Scottish matron when ten o’clock is going to strike.

So far, in spite of the different paths taken, Bybee and Pagliuca's hypothesis holds: intention dominates the early stages. Not so for the Swedish future marker komma att, diachronic statistics reveal: its beginning (16th-18th century) most frequently describes “involuntary reactions and non-agentive human activities”, e.g. förakta (despise), sova (sleep), rodna (blush) or höra (hear). (Hilpert, 2008, p.129-131)

Men man kommer att höra talas om honom! (But we are going to hear people talk about him!)

The next period (19th century) continues to feature involuntary emotional responses with gråta (cry), glädja (delight) or skratta (laugh); yet, intention is on the rise, or at least polysemy opens the door for intentional interpretation. For instance, intention, futurity and modality conflate in

Snart kommer nog andra att säga dig det, mumlade den gråskäggige. (Soon others will tell you so, mumbled the man with the grey beard.)

Only recently can komma att be “felicitously combined” with intentional activities: klara (manage, succeed) or skicka (send).

Ultimately, Hilpert's quantitative analysis succeeds in particular because it combines large number crunching with the pleasing and epistemologically sound examination of discrete corpus occurrences. In Swedish, abstraction from the notion of movement to that of future operates without the intermediary of intention.

There are, however, a few objections to the study of collexemes outlined above. Since large numbers are required, history is necessarily cut into thick slices. The only way to feel the nuances of evolution is still to consult discrete samples that line it up. Hilpert seems interested primarily in the characteristics, in particular the intention and agentivity content, of verbs frequently attracted by our auxiliaries. He compiles frequent collexemes, assesses their degree of intention against the dictionary - weak for sterven (die) or gråta (cry) or skratta (laugh), strong for nemen (take) -, and draws conclusions. Yet the degree of intention is always contextual: the actor intends to laugh and cry. Hilpert himself concedes this incidentally: he justifies an incongruous occurrence of a verb of intention, hämnas (to take revenge) in the first period of komma att by its denaturing by the context into denoting a “reaction to an emotional state”, in reference to

han är missnöjd och han kommer nog att hämnas!

(He’s angry, and he’s probably going to seek revenge!)

While requiring intention, the verb hämnas thus bears some resemblance to the other distinctive collexemes förakta (despise) and rodna (blush) which denote involuntary psychophysical responses. (Hilpert, 2008, p.129)

Finally, both Hilpert and Bybee and Pagliuca may be objected to for the sophistication of their argumentation; to examine whether “future meaning” historically derives from “meaning of intention” in movement-based futures, it is ultimately not necessary to recount the entire history of occurrences, and measure their degree of intention, either by calculation or patient exegesis. An look at the auxiliaries and common sense are enough: to go (gaan, be going to) or to come (komma att) require an agent, who intends to do so. There is always intention in verbs of movement. In their defense, these studies, notwithstanding the theoretical quibbles, are an encouragement to go through the corpora, feel the semantic nuances, and understand the usages, particularly in those of the languages evoked that are foreign to us.

Across languages, future tense develops its markers quite unanimously from verbs of movement or modality. In contrast, the semantic, morphological and syntactic pathways are very diverse. In particular, it is difficult, in view of the arguments put forward earlier, to conclude that there are universal stages of semantic development. Their authors are the scientific grammarians dreamed of by the late 19th century:

Als Aufgabe der wissenschaftlichen Grammatik können wir kurz die Erklärung der Formen einer Sprache bezeichnen und zwar in der Weise, wie sie entstanden sind. (Müller, 1976; in Heine, 1984, p.266)

“We can briefly describe the task of scientific grammar as the elucidation of the forms of a language, namely in the way they have developed.”

The future is a very special tense. Unlike the past and the present, it doesn't really exist: it doesn't exist yet. It is no surprise that it often carries a bit of that modal tone that connotes the real and the possible. Despite the variations, the idea of intention is never far away. It accompanies the early metamorphosis of Dutch gaan and English be going to from the literal to the figurative. It is obvious in desire-based futures, as English will. In all instances, the metaphor is very intuitive: intention wishes present thoughts to become future reality; spatial movement implies and evokes the time needed for the journey.

Language, we say, is in motion, and grammar, usage that has become form. This is rather paradoxical. If grammar is to accurately describe the rule system of a language, those rules and that language must be fixed. (It is impossible to take a snapshot of a body in motion.) If grammar is to prescribe the correct use of a language, its mandate permits no innovation. (Innovation requires - at least infinitesimal - dissidence from existing rules.) We can thereby claim that the grammar of a language in motion doesn't exist. It might be the invention humans infatuated in typology and completeness. The advent of intelligent machines is perhaps proof that, equipped with certain neural networks, one can finely process and generate language without awareness or abstraction of the presumed rules that regulate its usage. Naturally, if the existence of grammar is doubtful, so to is that of grammaticalization: language and its uses just continue their great intuitive movement, where mores, society, technology and communication intermingle.

References

Heine, B., Kuteva, T., & Narrog, H. (2017). Back again to the future: How to account for directionality in grammatical change. In W. Bisang & A. Malchukov (eds.), Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios (pp. 1-29). Berlin: Language Science Press.

Heine B, Reh M. (1984). Grammaticalization and Reanalysis in African Languages. Hamburg: Buske

Hilpert, M. (2008). Germanic future constructions: A usage-based approach to language change. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Traugott, Elizabeth C. (2012). Grammatical constructionalization: Rethinking grammaticalization in the light of constructionalization. Paper presented at the University of Santiago de Compostela, 17 October 2012.

Anthony Kroch, Beatrice Santorini, and Lauren Delfs. 2004. The Penn-Helsinki Parsed Corpus of Early Modern English (PPCEME). Department of Linguistics, University of Pennsylvania. CD-ROM, first edition, (http://www.ling.upenn.edu/hist-corpora/).

Bybee, Joan L., & Pagliuca, William. (1987). The evolution of future meaning. In A.G. Ramat, O. Carruba, & G. Bernini (eds.), Papers from the 7th International Conference on Historical Linguistics [Current Issues in Linguistic Theory 48] (pp. 109-122). John Benjamins