An odd coincidence

Intermingling | Past tense formation | Indo-European, Uralic and other languages

Leafing through the Wikipedia encyclopedia in Hungarian, the thought comes to us of the possibility, albeit frail, of a strange grammatical pattern, transversal to languages that even immemorial history separates. On the Gesta Hungarorum, for example, two medieval Hungarian manuscripts, priceless sources in Hungarian history and linguistics. The first (circa 1200, by a notary known as Anonymous) resonates with myths and legends: it evokes the Exodus from the ancestral land of Scythia. The second (circa 1283, by Simon of Keza), also known as the Gesta Hunnorum et Hungarorum, covers the period from the Hungarian conquest (of the Carpathian basin) to the time of King Ladislas IV.

Fiktív hősei a honfoglalás során pedig kitalált csatákat vívtak elképzelt népek és a honfoglalás korában a Kárpát-medencében nem létező hatalmak ellen.

“Its fictional heroes fought fictional battles against imagined peoples and powers that did not exist in the Carpathian Basin at the time of the conquest.”

(Wikipedia, Gesta Hungarorum)

What stands out in the highlighted Hungarian words is simply their featuring dental phonemes near the end of the word, and their congruence with the expression of the past: as the English translation testifies, these are the verbs conjugated in the past tense and past participles in the short passage (with the exception of the verb to be, from which an irregularity can be anticipated).

Let's understand more closely the Hungarian sentence, as always by identifying with English word group by word group. First, we highlight the minimal sentence, stripped of all modifiers, adverbial adjuncts of time and the long adverbial complements starting with against.

Fiktív hősei a honfoglalás során pedig kitalált csatákat vívtak elképzelt népek és a honfoglalás korában a Kárpát-medencében nem létező hatalmak ellen.

This kernel translates into …his heroes fought battles… with hősei (his heroes) a nominative possessive form of hős (3rd person singular possessor with plural possessed), vívtak (fought) our verb in the past indicative and csatákat (battles), as might be expected, an accusative plural. honfoglalás further refers to the Hungarian Conquest and our translation omitted the redundancy highlighted below.

Fiktív hősei a honfoglalás során pedig kitalált csatákat vívtak elképzelt népek és a honfoglalás korában a Kárpát-medencében nem létező hatalmak ellen.

során, an adverb, means during and kor-á-ban the inessive possessive of kor (time), so, in its time. (A very literal (improper) translation of a honfoglalás korában would be *in the Hungarian Conquest its time.)

Fiktív hősei a honfoglalás során pedig kitalált csatákat vívtak elképzelt népek és a honfoglalás korában a Kárpát-medencében nem létező hatalmak ellen.

Here, we have …fought battles (csatákat vívtak) against (ellen) people and powers (népek és hatalmak)… where the preposition ellen calls the nominative (plural) in népek and hatalmak.

Fiktív hősei a honfoglalás során pedig kitalált csatákat vívtak elképzelt népek és a honfoglalás korában a Kárpát-medencében nem létező hatalmak ellen.

The present participle létező is an attributive modifier of hatalmak and the clause it leads translates in to powers that did not exist in the Carpathian Basin (literally, *in the Carpathian Basin not existing powers) - which leave us with our past and past participles of interest:

Fiktív hősei a honfoglalás során pedig kitalált csatákat vívtak elképzelt népek és a honfoglalás korában a Kárpát-medencében nem létező hatalmak ellen.

kitalált is the past participle of the verb kitalál (to figure out, to invent, to make up) and is here attribute of csatákat, so invented (fictive) battles. Let's feel its conjugation table. The present tense (jelen idő) indefinite makes

én kitalálok

te kitalálsz

ő kitalál

mi kitalálunk

ti kitaláltok

ők kitalálnak

and we do notice the addition to the stem of a dental sound in the past tense (múlt idő) indefinite

én kitaláltam

te kitaláltál

ő kitalált

mi kitaláltunk

ti kitaláltatok

ők kitaláltak

Fiktív hősei a honfoglalás során pedig kitalált csatákat vívtak elképzelt népek és a honfoglalás korában a Kárpát-medencében nem létező hatalmak ellen.

The same can be said of elképzelt, past participle of elképzel (to imagine) whose past indefinite makes elképzelt in the third person singular. Eventually, vívtak is the third person plural past indefinite of vív. Its present counterpart is vívnak and the past “dental-suffix” is here clear too.

This already well-established trend is confirmed by the following extracts from the chronicles of Hungarian history.

Anonymus volt az első, aki az Attilától való származás lehetőségét megfogalmazta.

“Anonymus was the first who formulated the possibility of descent from Attila.”

(Wikipedia, Gesta Hungarorum)

Ennek a királynak az ivadékából sarjadt az igen nevezetes és roppant hatalmú Attila király.

“From this king's lineage descended the very famous and immensely powerful King Attila.”

(Gesta Hungarorum, ca. 1200)

Akkor a választásuk arra esett, hogy majd Pannónia földjét keresik fel. Erről ugyanis a szállongó hírből azt hallották, hogy az Attila király földje, akinek az ivadékából Álmos vezér, Árpád apja származott.

“Then their choice fell on seeking the land of Pannonia. For they had heard from rumors that it was the land of King Attila, from whose line descended Chief Álmos, Árpád's father.”

(Gesta Hungarorum, ca. 1200)

Az Úr megtestesülése utáni négyszázegyedik, a magyarok Pannóniába történt bejövetelétől számított huszonnyolcadik esztendőben a magyarok, vagyis a hunok a rómaiak szokása szerint egyetértő akarattal királyul emelték maguk fölé Attilát, Bendegúz fiát, aki előbb a kapitányok közé tartozott;

“In the four hundred and first year after the Lord's incarnation, and in the twenty-eighth year after the Hungarians' entry into Pannonia, the Hungarians, or rather the Huns, following Roman custom, by unanimous will raised Attila, son of Bendegúz, who had previously belonged among the captains, as king above themselves.”

(Képes Krónika, 1358)

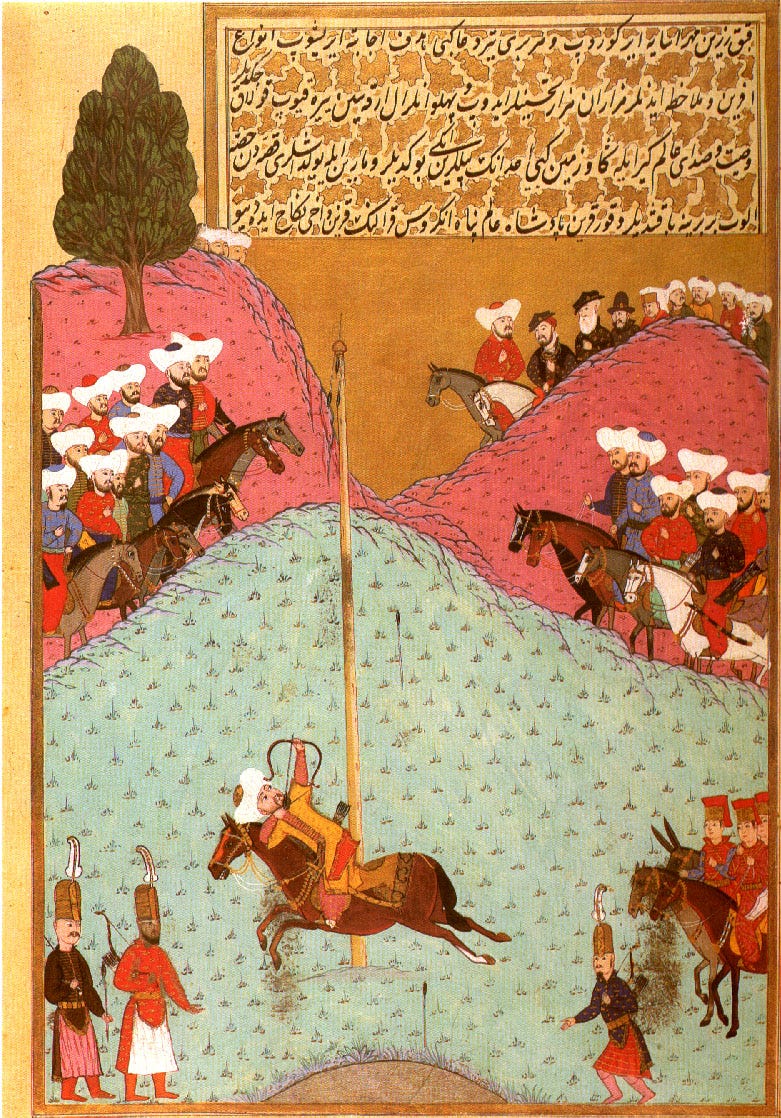

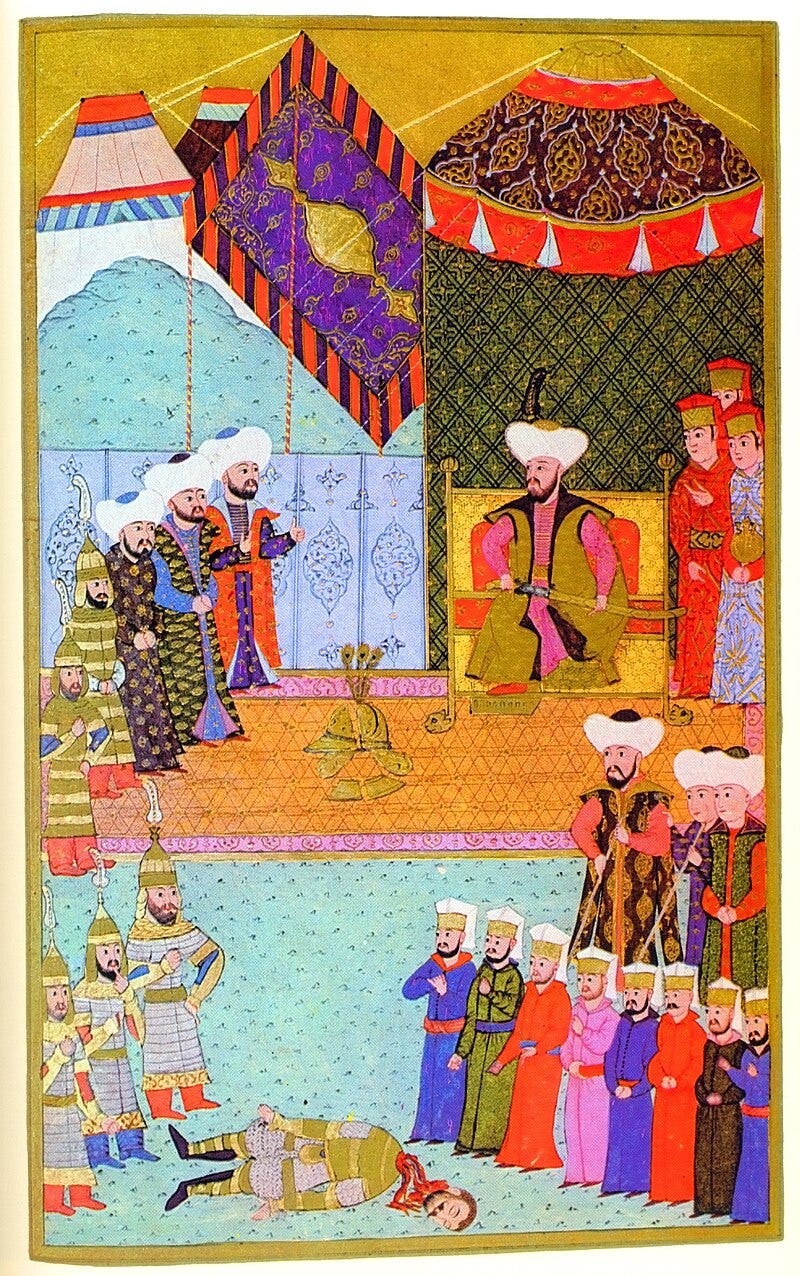

The Képes Krónika (Chronicon Pictum), from which the last passage is taken, continues to recount the Hungarian myth of origins. The collection of illustrated historical chronicles written by Marc de Kalt in 1358, on commission from King Louis I, is based on a lost manuscript of the Gesta Ungarorum dating from the end of the 11th century and the time of Saint Ladislas. It endeavors to recount the continuity of the Hun and Hungarian reigns. Unequivocally, emelték and tartozott are the two past forms translated by raised and had belonged respectively. By contrast, the use of the past participles történt and számított, not explicitly rendered in the English translation, requires clarification. történt (happened) is used as an attributive adjective to the ablative bejövetelétől (from the entry): történt bejövetelétől is literally (and improperly) *from the happened entry [into Pannonia], that is, more regularly, after the entry [into Pannonia] had happened, where a natural and fluid translations further omits had happened, as it is redundant with the preposition after. Similarly számított (counted) is employed as an attributive adjective to esztendőben. Whereas the suffix -től betrayed the ablative, -ben signals the inessive, the case of the space in which we are. huszonnyolcadik esztendőben means in the 28th year and a fluent translation here again omits the excess zeal in a literal *in the 28th counted year.

Ultimately, the past tense, the grammar book tell us, “is expressed with the suffix -t or -ott/-ett/-ött and inflects for person and number.”

We have spoken at length about the dental suffix that runs through the formation of past tense in Germanic languages, a legacy of Proto-Germanic. Observing the phenomenon outside the spectrum is at least intriguing, and calls for further comparative studies.

Here again, we prefer historical accounts, for their several virtues. Firstly, they abound in past-tense forms, which are presently our main interest. Second, they are particularly propitious for comparative linguistics: they teem with proper nouns and dates, highly recognizable from one language to another, which act as landmarks, secure rivets on which parallel exegesis can be fixed. The following concerns the peace negotiations between the Ottoman Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary in 1444:

6 Mart 1444'te ilk müzakereler başladı. Ardından 24 Nisan 1444'te Kral Ladislas II. Murad'a müzakereleri kabul ettiğini belirten bir mektupla birlikte elçisi Stojka Gisdaniç'i Edirne'ye gönderdi. Esirlerin teatisinde varılan uzlaşının ardından toprak meseleleri müzakere edildi. Osmanlılar, Macarların 1443-1444 seferinde kaybettikleri Güvercinlik (Golubaç) ve Semendire'nin iadesini temine çalıştılar. Ancak Karaman Beyi İbrahim'in Anadolu'daki saldırıları nedeniyle apar topar 12 Haziran'da mevcut koşullarda barışa razı oldular.

Perusing the text, however sybaritic before translation, is enough to intrigue us. The final words of the five sentences are not entirely random: they have similarities of form. başladı, gönderdi, edildi all end in -di while çalıştılar and oldular share the ending -lar, or even -d/t + vowel + lar. A sentence-ending verb cannot come as a surprise to a Germanist, of whom the learner of Old Norse is a close relative. If these five Turkish forms were our past tense verbs, we would certainly be holding our dental suffixes. Let's take a look at the English translation, and indulge in our favorite exercise: parallel reading and comprehension. We highlight verbs in the past tense.

“The initial negotiations began on March 6, 1444. Then on April 24, 1444, King Ladislas sent his envoy Stojka Gisdanić to Edirne with a letter indicating to Murad II that he accepted the negotiations. After reaching an agreement on the exchange of prisoners, land issues were negotiated. The Ottomans tried to secure the return of Güvercinlik (Golubac) and Smederevo, which the Hungarians had lost in their 1443-1444 campaign. However, due to the attacks of Ibrahim, Bey of Karaman, in Anatolia, they hastily agreed to peace under the existing conditions on June 12.”

The first sentence is clear: under our hypothesis, başladı is the verb began. That leaves a date, 6 Mart 1444'te, and a subject noun phrase, ilk müzakereler for the initial negotiations. Let's test our proficiency in a language we didn't know a few hours ago on the second one. We emphasize everything we recognize transparently.

Ardından 24 Nisan 1444'te Kral Ladislas II. Murad'a müzakereleri kabul ettiğini belirten bir mektupla birlikte elçisi Stojka Gisdaniç'i Edirne'ye gönderdi.

“Then on April 24, 1444, King Ladislas sent his envoy Stojka Gisdanić to Edirne with a letter indicating to Murad II that he accepted the negotiations.”

We also assumed that gönderdi to be a past tense verb. Its position near Stojka Gisdaniç'i, which would then serve as its direct object, speaks for its being the main clause’s verb, sent. Ardından could well start the time adjunct given its situation (then). This leaves his envoy […] with a letter indicating […] that he accepted the negotiations to our mapping speculation. elçisi is a good candidate for [Stojka Gisdaniç’s] envoy given the proximity in location and ending, -i. The treasure hunt continues. If elçisi Stojka Gisdaniç'i is indeed his envoy, object of sent, the -i ending might be typical of the direct object case. The exegesis of our first sentence had expedited the correspondence of ilk müzakereler with the initial negotiations. müzakereleri is an obvious match for negotiations, this time in the accusative as a direct object of accepted. All that remains is with a letter indicating […] that he accepted. Firstly, we can assume with a letter to be closest to the phrase its accompanies, elçisi Stojka Gisdaniç'i (his envoy Stojka Gisdanić) and that he accepted closest to its presumed direct object, müzakereleri (the negociations). Secondly, the ending of ettiğini could again betray an accusative. In with a letter indicating […] that he accepted, a letter is no accusative, maybe an instrumental case. The only element that can carry the accusative is acceptance, a nominalized flavor of the verb phrase that he accepted, direct object to indicating. From there on, we are content with assessing electronically our guesses. bir mektupla birlikte is indeed with a letter, -la marking the instrumental case. In kabul ettiğini, kabul is the substantive acceptance, the prefix et- verbalizes it while -tiğ- forms the past participle and -ini marks the accusative possessive. Literally, something such as *his (having) accepted. The suffix -en in belirten marks the present participle, indicating.

Incidentally, we increased our lexicon, inferred possible desinences of the nominative (plural), accusative and instrumental, observed how we verbalize a noun, and form the possessive and the past participle, among others. It is in this way, guided by curiosity and bilingual reading, that we believe it is most delectable and effective to learn a new language - rather than through primary, rebarbative exercises ordered in booklets for novices. We have set some foundations. We may forget Turkish for a long time, but if we come back to it, we will already feel a little at home.

We can now draw some conclusions from our observations. The past tense of Turkish verbs (at least those we have encountered) is systematically formed with stem + suffix di/du + person marker (possibly null). We have namely

başla-dı-ø: stem (başla-) + past suffix (-dı) + null person marker

gönder-di-ø: stem (gönder-) + past suffix (-di) + null person marker

edil-di-ø: stem (edil-) + past suffix (-di) + null person marker

çalış-tı-lar: stem (çalış-) + past suffix (-tı) + person marker (-lar)

ol-du-lar: stem (ol-) + past suffix (-du) + person marker (-lar)

where the person markers -ø and -lar mark the 3rd person singular and plural respectively. (An attentive mind will wonder about başla-dı-ø's lack of congruence with its plural subject ilk müzakereler. Turkish, it seems, takes some license with subject-verb agreement, and the singular is preferred for an inanimate plural subject. Here, the subject can also be interpreted as a collective singular concept: English can after all also say the negotiations began.)

Ultimately, the past tense suffix in Turkish will be chosen among

-di/-dı/-du/-dü

-ti/-tı/-tu/-tü

based on some vowel harmony rules. A watered-down form of vowel harmony is well known to practitioners of Old Norse or Icelandic: the phonetic u- and i-omlyd (umlaut), which we shall review shortly. In short, a word's vowels (especially during declension) adjust in height, frontness or roundedness, to be more “in tune” with each other.

The Hungarian-Ottoman peace of 1444 is soon breached by Hungarian King Władysław III. The battle of Varna proves fatal to him: Murad II’s triumph paves the way for the Ottoman takeover of Constantinople in 1453. Ottomans too are mindful of dynastic historiography. While Hungarians trace a Hunnic lineage through the Gesta Hungarorum, Murad II models himself after the legendary Ghazi kings:

He drew from the noble behavior of the nameless Caliphs in the Battalname, an epic about a fictional Arab warrior who fought against the Byzantines, and modelled his actions on theirs. He was careful to embody the simplicity, piety, and noble sense of justice that was part of the ghazi king persona. […]

Murad II successfully painted himself as a simple soldier who did not partake in royal excesses, and as a noble ghazi sultan who sought to consolidate Muslim power against non-Muslims such as the Venetians and Hungarians.

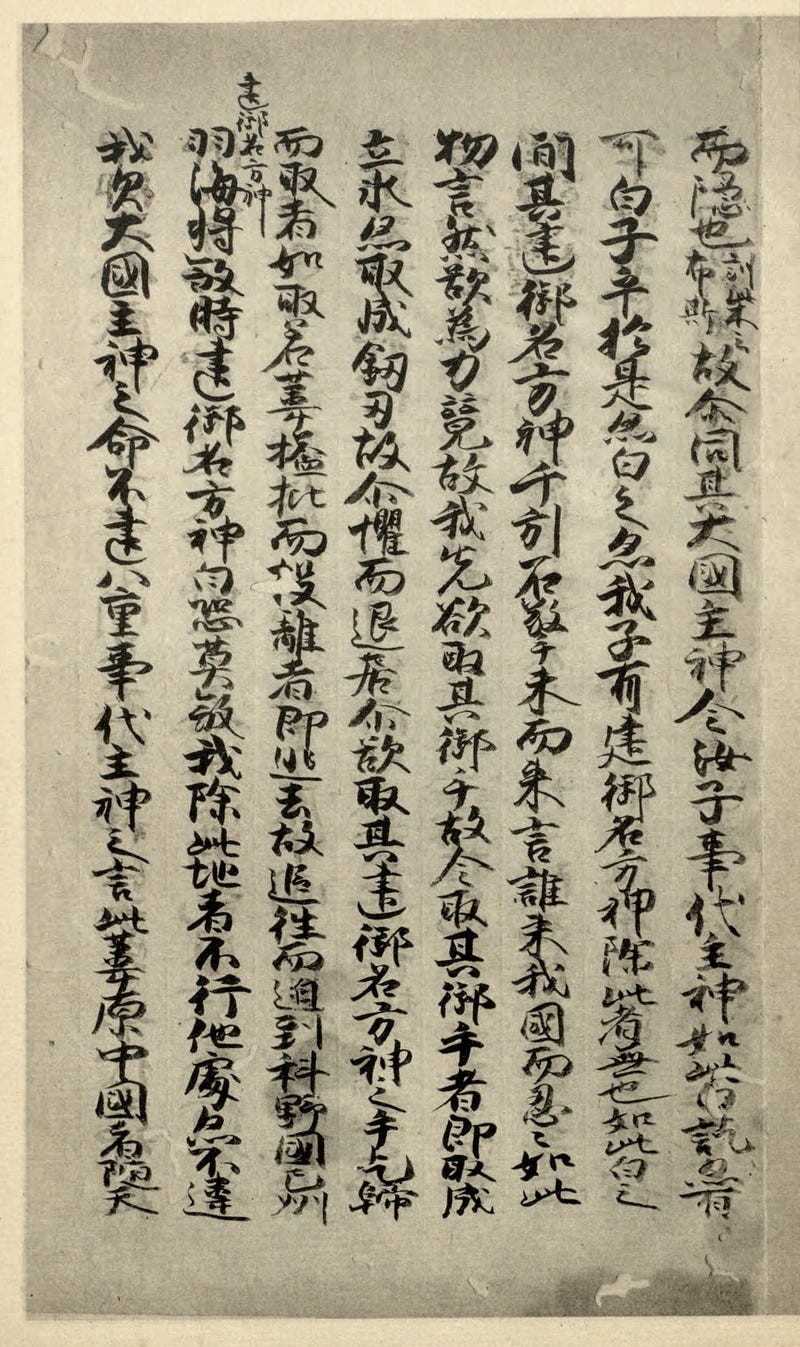

History books and myths also served imperial Japan. The Kojiki (古事記, Archives of Ancient Affairs) and the Nihon Shoki (日本書紀, Chronicles of Japan) pass for the oldest chronicles: the former is commissioned by the imperial reign and completed in the early 8th century. It legitimizes Yamato's rule by a divine lineage, and noble families of a new rank society by a chosen genealogy.

Let’s read an account for an episode concerning Emperor Jimmu, the legendary first emperor of Japan according to the Kojiki.

そして龍田へ進軍するが道が険阻で先へ進めなかった。そこで東へ軍を向けて胆駒山を経て中洲(大和国)へ入ろうとし、この地を支配する長髄彦と孔舎衛坂で戦った。 戦いに利なく、長兄の五瀬命は流れ矢に当たって負傷した。そして日の神の子孫の自分達が日に向かって(東に向かって)戦うことは天の意思に逆らうことだと悟ることとなった。彦火火出見尊は兵を集めて草香津まで退き、再び海路南へと向かった。

Guided by our Germanist thoughts, we notice a strange pattern: (almost) all sentences finish with a similar syllable,った (-tta). A closer look further shows a certain recurrent vicinity of the symbols か and な,

そして龍田へ進軍するが道が険阻で先へ進めなかった。そこで東へ軍を向けて胆駒山を経て中洲(大和国)へ入ろうとし、この地を支配する長髄彦と孔舎衛坂で戦った。 戦いに利なく、長兄の五瀬命は流れ矢に当たって負傷した。そして日の神の子孫の自分達が日に向かって(東に向かって)戦うことは天の意思に逆らうことだと悟ることとなった。彦火火出見尊は兵を集めて草香津まで退き、再び海路南へと向かった。

Here is an electronic translation:

“When they advanced to Tatsuta, the road was too treacherous to proceed. They then turned the army east, passing through Mount Ikoma, attempting to enter Nakasu (Yamato Province), and fought with Nagasunehiko who controlled this area at Kosae slope. The battle was not favorable, and their eldest brother Gose no Mikoto was wounded by a stray arrow. They then realized that fighting while facing the sun (facing east) as descendants of the sun deity was against heaven's will. Hikohohodemi no Mikoto gathered his troops, retreated to Kusaka-tsu, and again headed south by sea.”

Let's decipher the sibylline

そして龍田へ進軍するが道が険阻で先へ進めなかった。

by means of our ordinary approach to language learning. The piece translates into

When they advanced to Tatsuta, the road was too treacherous to proceed.

Asking semiconductors for a translation of “they advanced to Tatsuta” we are given 龍田へ進軍する, which fits our passage perfectly.

そして龍田へ進軍するが道が険阻で先へ進めなかった。

We don’t find here the recurrentった that we might hope to be a past tense marker. The verb 進軍する , we learn, is indeed a narrative present tense. Next, a proposed translation for “the road was treacherous” is 道が険阻だった which we spot almost entirely in the original

そして龍田へ進軍するが道が険阻で先へ進めなかった。

道が険阻 may be assume to match “the road… treacherous” while the verb asks for clarification. In your remnant 進めなかった, な (na) marks the negation, 進め is the modal can advance, and the whole なかった (nakatta) marks the negative past tense. In fact, the Japanese seems to literally say *the road treacherous […] could not advance where something indicating causality is clearly missing: the role is filled by the conjunctionで (de) which can be translated by being:

…the road being treacherous, (they) could not advance

Incidentally, we have illustrated once more how a parallel inspection, driven by curiosity, of new language and English makes the opaque clearer. We claim this the most fruitful and funniest way to learn new languages generally.

Upset by Germanist ideas, we have been struck so far by a strange coincidence: that of dental suffixes for past tense formation in Hungarian, Turkish, and Japanese. As mentioned earlier, a dental suffix runs through the Germanic spectrum in the formation of the past tense of weak verbs, and the pattern is assumed, by Ringe (2017) in particular, to be a Proto-Germanic legacy. (Here, we were looking at how the Proto-Germanic weak verb classes identified by Ringe prolong into Old Norse.) Proto-Germanic is assumed to have formed its past indicative and subjunctive with a *-d- (perhaps a *-dēd-) suffix. Its past indicative would have followed the following pattern:

Past tense indicative suffix-ending(s)

Sg -d-ǭ

-d-ēz

-d-ē

Pl -d-ū

-d-u-diz

-d-u-m, -d-u-d, -d-u-n

We shall soon come back to this Proto-Germanic phenomenon and the efforts that have been made to shed light on its origins. But for now, let's focus on our coincidence. Apart from a certain dental suffix in the formation of the past tense, Hungarian, Turkish and Japanese have in common that they share no Indo-European genealogy. Consensus places Hungarian in the Ugric branch of a Uralic family and derives it from a Proto-Ugric spoken “from the end of the 3rd millennium BC until the first half of the 1st millennium BC, in Western Siberia, east of the southern Ural Mountains”. Turkic languages on the other hand are thought to have derived from some Proto-Turkic that would have emerged between the Transcaspian steppe and Manchuria around 2500 BC. The so-called Japonic languages encompass Japanese and the indigenous languages of the Ryukyu Islands, that are assumed to have originated from a Proto-Japonic brought to the archipelago in the early 4th century BC by settlers stemming from the Korean peninsula.

Nevertheless, the history of linguistics abounds in hypotheses and controversies around a potential kinship between these three language families, with a recent resurgence of interest fueled by the unprecedented computational possibilities of modern times. By the late seventeenth century already, the outlines of an Altaic family were being discerned, grouping together Turkic, Mongolic and Tungusic. The 18th century proposed that it be rallied by Uralic languages on the one hand, and Japanese and Korean on the other. Let's first consider Japanese language specialist Alexander Vovin's arguments against the latter hypothesis, as he shifted from advocating to criticizing it. In short, he denounces the lack of sufficient evidence, and charges vehemently (Vovin, 2009) certain recent scholarly works whose attempts at proof he finds fundamentally flawed. Here we are at the very core of the dispute: what proof is necessary and sufficient to demonstrate an indisputable kinship between two (families of) languages? According to Vovin (2011, p.6; emphasis added):

… the demonstration of a [genealogical] relationship is only possible by either showing the existence of common paradigmatic morphology, and/or by demonstrating the existence of regular phonetic correspondences within the basic vocabulary.

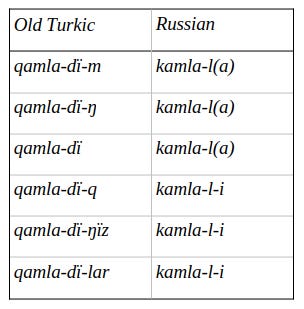

Regular morphological correspondences between two words (from different languages) being compared are not enough : such correspondences must also not be due to borrowing; be “predictive-productive”, i.e. be systematic and extend to inflection and overall word formation based on active (productive) rules (thereby predictive of new word formation); leave no unaccounted segment; come with semantic correspondence, supported not by bare word-lists but philological evidence, corpus occurrences, and cultural context. As such restrictions demand hard work, it is easy to be lulled by similarities that are mere borrowings or happenstance; and hasty judgment could justify nearly any adoption by the Altaic family. If we were to follow Robbeets' reasoning in its ultimate consequences, Vovin scorns, we would add Russian: Robbeets claims a Proto-Altaic denominal verbal (i.e. formative of verbs from substantives) suffix *-la- on the basis of a Proto-Japonic *-ra- yielding Old-Japonic -r-, Turkic *-lA-, Mongolic *-lA-, and Tungusic *-lA-. Vovin further notes the similarity between Russian kamla- “to shamanize” and Turkic qam-la- “to shamanize” derived from qam “shaman”. Those verbs form their respective past as follows

and Vovin (2011, p.1-2) concludes

… stems are identical but the paradigms are not: derivational verbal morphology is easily borrowed, but inflectional is not.

In short, a conclusive resemblance must extend to inflection. The borrowing (rather than the inheritance) of a derivation rule is further betrayed by its loose systematism. Mongolian has boγorla- “cut the throat” visibly corresponding to Old Turkic boγuz-la- with same meaning derived from boγaz~ boγuz “throat”; Mongolian ögütle- “advise” to Old Turkic ögüt-le- “advise” from ögüt “advice”; or Mongolian čiŋla- ~ čiŋna- “listen” to Old Turkic tïŋ-la- “listen” from tïŋ “listening”. Yet, Vovin tells us, there are no Mongolic root words meaning throat, advice, or listening which boγorla-, ögütle- or čiŋla- could be derived from by appending a suffix -la: these verbs were borrowed, and only later did the rule become productive in Mongolian, with, for example, üge-le- “to say” from üge “word”, as the -la/-le suffix was eventually “segmented and began to be used after pure Mongolian nominal roots”.

Establishing a language family is an ambitious task, as it faces nearly impossible criteria. For Giorgio Orlandi (2020, p.43), another detractor of an Altaic Japanese, “one of the universal criteria for demonstrating the integrity of a language family”, captured in one formula, is “confidentially eliminating chance, borrowing, and other non-genetic factors”. We near tautology: to demonstrate that a resemblance attests to kinship, one must eliminate the possibility of all alternative explanatory factors, all of which are, by definition, non-genetic. Later, Orlandi (2020, p.52) specifies: two languages are genetically related if the ancestor language, the protolanguage from which both derive, is “recoverable only by means of specific linguistic techniques which seek to reconstruct [the] rules and restructurings" that mold their respective evolution after the branching off. These techniques are mainly internal and external reconstruction. Internal reconstruction compares, internally to one language, “allomorphs in order to arrive at a reconstructed invariant form of a morpheme” while external reconstruction, the “comparative method”, seeks to reconstruct the ancestor from word matching across languages. Published in 2003, the Etymological Dictionary of the Altaic Languages (Statosin et all.), “a huge work in three volumes, containing 2,800 etymologies” is thus regarded by its authors as the definitive end of the debate:“the very fact that it is possible to compile a dictionary of common Altaic heritage, they say, appears to be a proof of the validity of the Altaic theory”. Yet Orlandi warns: reconstruction can easily lapse into “teleological exercise” or a “speculative etymological construct”. It is particularly Statosin's phonetic reconstruction that Orlandi seem to dislike. The sound laws governing the derivation of the daughter languages must be both typologically plausible and consistent with the principles of naturalness - established pattern of language evolution are observed - and minimality - each sound change affects only one phonetic feature at a time. And Orlandi concludes: Statosin's reconstruction is not sufficient, but neither is reconstruction necessary.

While the Trans-Himalayan family is widely accepted (Greenberg 1996: 134, LaPolla 2001: 225), a complete reconstruction of Proto-Trans-Himalayan is still unavailable at the moment. This proves that the “reconstruction” of a Proto-language does not imply the validity of that language family, and vice versa.

It seems that Altaists weave by day the demonstration that anti-Altaists unweave by night: like Penelope's knitwear, the scholarly talk can go on for a long time.

We understand that an unsettling similarity between two languages of humanity can be due to heritage, borrowing or chance - and that proof can be epic. But are we sure that nothing is missing from the picture? Some interlanguage similarities come to our minds, which none of the three above-mentioned factors primarily explains: pathways of grammaticalization. Gradually, usage transmutes, via abstraction, a lexical element into a grammatical one, a content-word into a function-word. Thus, numerous markers of future tense across languages derive, along recurrent morphological, semantic and phonetic paths, from verbs of movement or intention.

Heine and Kuteva (2002) catalogue a host of such semantic source-target associations: too much coincidence to invoke luck, while anachronistic universality defies both borrowing from contact and heredity. As we have seen, grammaticalization arises from communication needs. The paths of species evolution require the increasingly effective expression of increasingly abstract notions, which find their way by metaphor from the concrete: the time of movement projects into the future, so that progressive usage fixes the English “is going to”, the Dutch “gaan”, the Swedish “komma att” as future tense auxiliaries. The constants of the grammaticalization phenomenon and its modalities - source-target pairs, morphological, phonetic and semantic paths - thus respond to species modalities of cognition and communication, and to their evolutionary trajectories sculpted by interdependent biology and culture. Among these cognitive universals, we also find the hypothetical “universal grammar”, an innate propensity for language and an innate notion of its functional categories. According to a Strong Minimal Hypothesis, what makes human language unique is the hierarchical structure of its syntax: the emergence of its merge function, together with the cognitive and sensory-motor capacities underpinning thought and expression, propel our species on its distinctive trajectory. (It makes it possible to assemble the and apple in the set {the, apples}, which further combines to ate in {ate,{the, apples}}, etc.) How Could Language Have Evolved? (Bolhuis, Tattersall, Chomsky & Berwick, 2014), where interests from neurobiology, anthropology and linguistics converge, seem to call on future science to clarify the potential genomics of such merge function.

With merge […] the basic properties of human language emerge. Evolutionary analysis can thus be focused on this quite narrowly defined phenotypic property, merge itself, as the chief bridge between the ancestral and modern states for language. Since this change is relatively minor, it accords with what we know about the apparent rapidity of language’s emergence.

Although its malfunctions “produce speech deficits in modern people”, the gene FOXP2, the authors recall or deplore, can no longer be “regarded as “the” gene “for” language” as many others intermingle in “its normal expression”. The desire is palpable to find its theoretical replacement, a gene of the decisive merge function. Eventually, beyond the brain, another obvious biological universal is that of the vocal tract, which conditions the phonological possibilities and drifts of languages.

In short, it is not surprising that languages resemble each other: they are human. Perhaps there is a biology of past tense formation, a genetics of the past tense forming dental suffixes that at least four very different kind of languages seem to feature. Let's sketch out two ideas for pursuing our investigation. We have taken a close look at the grammaticalization of future markers: our suffix could be a result of that of past expression. One of the constant processes of grammaticalization, as we have seen, is semantic, morphosyntactic, and phonetic coalescence, which the African dialects of !Xun illustrate well at work: the Proto-!Xun (reconstructed) verbs of motion *gǀè (come) and *ú (go) merge with the conjunctions *kà and *tà or the transitive suffix *-ā to produce future tense markers, for instance in ò-tāǁé (will die) and oga gǀyee (will come) that respectively derive from *ú tā ǁé (go and die) and *ú kā gǀè (go and come).

Let's imagine our dental past tense markers originating from the same slow coalescence and abstraction from some kind of lexical items with concrete meaning. Their phonetic similarity across languages could then result from that of their source words. What could justify interlanguage congruence of sounds and meaning? Well, here also, theories and literature abound. Modern “sound symbolism” and its sophisticated laboratory experiments continue to enliven the didactic disputes of Plato's Cratylus.

References

Geréb, L. (Trans.). (1993). Képes Krónika: A magyarok régi és legújabb tetteiről, eredetükről és növekedésükről, diadalaikról és bátorságukról. (T. Tarján, Ed.). Magyar Hírlap és Maecenas Kiadó.

Ringe, D. (2017). From Proto-Indo-European to Proto-Germanic (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Vovin, A. (2009). Japanese, Korean, and Other 'Non-Altaic' Languages. Central Asiatic Journal, 53(1), 105-147.

Vovin, A. (2011). Why Japonic is not demonstrably related to 'Altaic' or Korean. Paper presented at the 20th International Conference on Historical Linguistics (ICHL XX), Osaka, Japan, July 30, 2011.

Heine, B., & Kuteva, T. (2002). World Lexicon of Grammaticalization. Cambridge University Press.

Bolhuis, J. J., Tattersall, I., Chomsky, N., & Berwick, R. C. (2014). How Could Language Have Evolved? PLOS Biology, 12(8), e100193434.